When I first picked up a trowel, I didn’t realise I’d also need to advocate. I remember when I first fell in love with archaeology. I was in a practical and I held some tiny carved elephants. I can’t remember what they were made out of – clay? stone? – but I loved them. At this point in my life, I didn’t realise how hard it would be.

I had a bad nausea issue and the challenges that come with being autistic, but in my second and third years, it got a lot harder. A chronic pain diagnosis changed my perspective. What I felt I could once do and enjoy, felt out of reach.

I remember being at a field school with a friend, sitting in the most comfortable positions for us – the positions with the least amount of pain. We were quickly told that how we were sitting was ‘incorrect’ and therefore ‘bad’. That moment stuck with me – we weren’t sat on the section and other archaeologists had no issue with how we were sat. Who decided what was the right and the wrong ways to work in the field? Why wasn’t accessibility factored into that conversation?

When I first got my chronic pain diagnosis, it felt like everything was over. That was it – no more digging. Therefore could I even be an archaeologist? It took a lot of reflecting before I realised I could and that archaeology is so much more than excavation. There’s plenty of lab work, post ex, museum and admin work. All these areas keep the field alive. And, if you think about it, it isn’t that hard to simply adapt how you conduct fieldwork. These barriers aren’t just physical, it had a big emotional impact.

I am clearly not the first, and I will not be the last, to experience this. The Disabled Archaeologist Network is proof that change is happening. Disabled archaeologists can often bring unique insights to the field, simply through having different life experiences. Our life experiences shape our interpretations of the past.

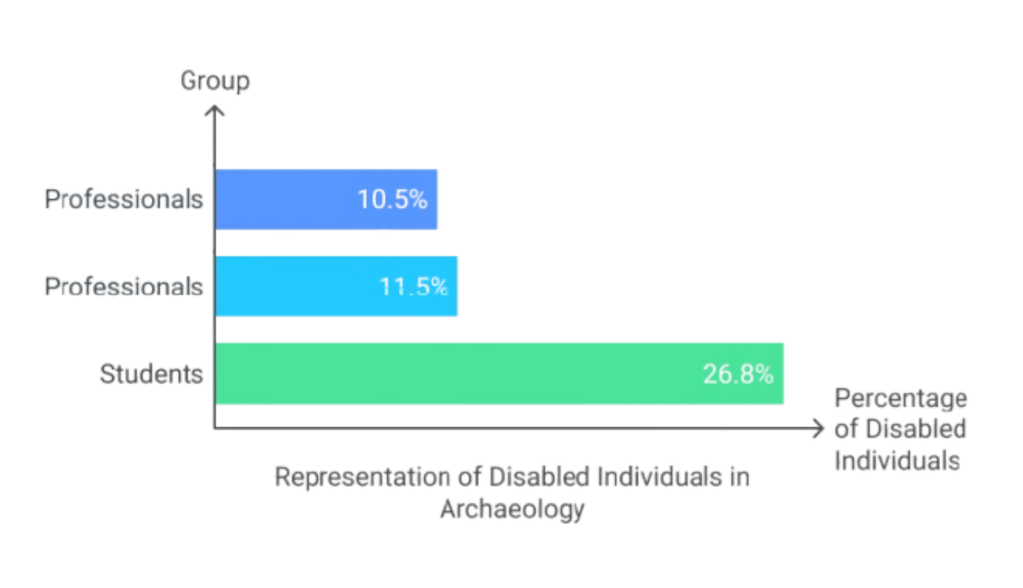

Yet, statistics highlight an issue. Profiling the Profession (2019-2020) and CIfA (2020) found that between just 10.5% – 11.5% of people report as disabled. However, when it comes to archaeology students, this number jumps to 26.8% – over a quarter. This means that somewhere along the way, disabled archaeologists either leave the profession, or do not feel comfortable disclosing their disability. This needs to change.

There is a lot of hope though. Adaptive tools are being developed. Thoughtful planning for accessibility is becoming more common. None of this happens in isolation – this is all due to community and advocacy.

My hope is that universities and organisations will continue to make these adjustments, not as an afterthought, but as a necessary part of the profession.

If you’re a disabled archaeologist or student, know that you’re not alone.

If you are interested in reading more about Ableism in Archaeology, I recommend reading:

Heath-Stout, L., Kinkopf, K.M. and Wilkie, L.A., 2022. Confronting Ableism in Archaeology with Disability Expertise. SAA Archaeological Record, 22(4), pp.13-17.

Leave a comment